Meru Virtual World Architecture |

||

|

People:Stanford: Daniel Horn, Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Tahir Azim, Behram Mistree, Bhupesh Chandra, Lily Guo, Philip LevisPrinceton: Jeff Terrace, Xiaozhou Li, Mike Freedman Win32 client work by: Matteo Borri | ||

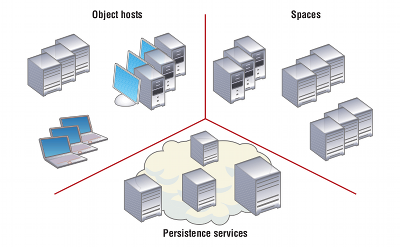

Introduction:We believe that one of the next major application platforms will be 3-dimensional, online virtual worlds. Virtual worlds are shared, interactive spaces. Objects inhabit the space, have programmable behaviors, and can discover and communicate with other objects. Users commonly experience the world through an avatar and can interact with objects in the world, much as they would in the real world. Many currently deployed applications are virtual worlds: multiplayer online games such as World of Warcraft and social environments such as Second Life are popular examples. Other examples include environments for virtual collaboration, distance learning applications, and augmented reality.Unfortunately the early evolution of virtual worlds has been ad hoc. They have completely independent constructions, share few architectural aspects, and offer little or no interoperability. Because these systems are designed for very specific applications, each suffers from at least one of poor scalability, centralized control, and a lack of extensibility. The Meru Project is designing and implementing an architecture for the virtual worlds of the future. By learning how to build applications and services before they are subject to the short-term necessities of commercial development, we hope to avoid many of the complexities other application platforms, such as the Web, have encountered. We're currently working on the following projects: |

||

| ||

Space Architecture:Currently we are focusing on the architecture of space servers. They provide four basic services:

| ||

Scripting:In a seamless, scalable, and federated virtual world scripted objects are distributed across many hosts and users may generate and host scripts. Communication between objects via asynchronous messages is the norm, and objects may not trust each other. These challenges make popular scripting languages poorly suited to this domain. Most existing languages designed for virtual worlds are ad hoc and often lack even basic features for event-driven programming, code reuse, and interactive scripting.We are developing Emerson, a scripting language based on JavaScript. Emerson addresses these challenges with three core design concepts: entity-based isolation and concurrency, an event driven model with concise and expressive pattern matching to find handlers for messages, and strong support for example-based programming within the live virtual environment. | ||

Content Distribution for Virtual Worlds:Much of the content that makes up a virtual world is long-lived, static content: meshes, textures, scripts, and audio. Content distribution networks address the problem of efficiently serving these assets to millions of clients.Virtual worlds have a few properties which suggest a different CDN design might be warranted. First, most content can be split into levels of detail and accessed incrementally. For instance, a texture can be displayed at lower resolution before the entire texture has been downloaded. Further, the client may not request all chunks: a higher resolution version of the texture might not improve the rendering because the mesh is too far away for it to be noticable. Second, the relative importance of requests varies quickly over time. Unlike the resources on a web page, which are all required to display the page, the content required to display a virtual world may vary quickly. If the user turns, the relative importance of different meshes and textures in the scene change suddenly. Still, out-of-view elements should still have some priority since the user may turn back towards them soon. Finally, virtual worlds have spatial locality that could be exploited by the CDN: resources that are geometrically nearby in the world are likely to be requested by the same client. For instance, the meshes for objects that are next to each other will likely be requested by all avatars in the region. We are building a CDN which exploits these features, as well as a client library to ease interaction with the CDN and high frequency updates to requests. | ||

Graphics:A client displaying a virtual world must decide which assets to download and display, taking into account the effect that asset (or lack of the asset) will have on the fidelity of the world, the current and possible viewpoint of the user, the size of the content (both for download and as stored on the graphics card), and that the data must be streamed from the CDN.We are building a flexible graphics asset manager which can account for these challenges and allows us to experiment with different algorithms for prioritizing and downloading assets and LODs of assets. Built on top of our CDN client library, it will be able to quickly update the priorities of assets. The algorithms could take into account resource constraints of the graphics hardware, perceptual metrics taking into account the objects the assets are associated with, the available levels of detail, and the time to transfer the data from the CDN. | ||

Publications:[1] Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Tahir Azim, Behram F. T. Mistree, Daniel Reiter Horn, Jeff Terrace, Philip Levis, and Michael J. Freedman. "A Scalable Server for 3D Metaverses", To appear in Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference (ATC '12). [2] Jeff Terrace, Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Philip Levis, and Michael J. Freedman. "Unsupervised Conversion of 3D Models for Interactive Metaverses", Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME 2012) [3] Behram F. T. Mistree, Bhupesh Chandra, Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Philip Levis, and David Gay. "Emerson: Accessible Scripting for Applications in an Extensible Virtual World", Proceedings of the ACM international conference on Object oriented programming systems languages and applications (Onward 2011). [4] Bhupesh Chandra, Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Behram F. T. Mistree, Philip Levis, and David Gay. "Emerson: Scripting for Federated Virtual Worlds", Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Games: AI, Animation, Mobile, Interactive Multimedia, Educational & Serious Games (CGAMES 2010 USA). [5] Daniel Horn, Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Tahir Azim, Michael J. Freedman, Philip Levis, "Scaling Virtual Worlds with a Physical Metaphor", IEEE Pervasive Computing, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 50-54, July-Sept. 2009, doi:10.1109/MPRV.2009.54 | ||

Technical Reports:[6] Daniel Horn, Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Behram F.T. Mistree, Tahir Azim, Jeff Terrace, Michael J. Freedman, and Philip Levis "To Infinity and Not Beyond: Scaling Communication in Virtual Worlds with Meru", CSTR 2010-01 5/11/09 |